An America of shepherds, pelotaris and boarders: the Basques of the USA celebrate their big festival

25 Jul 2025

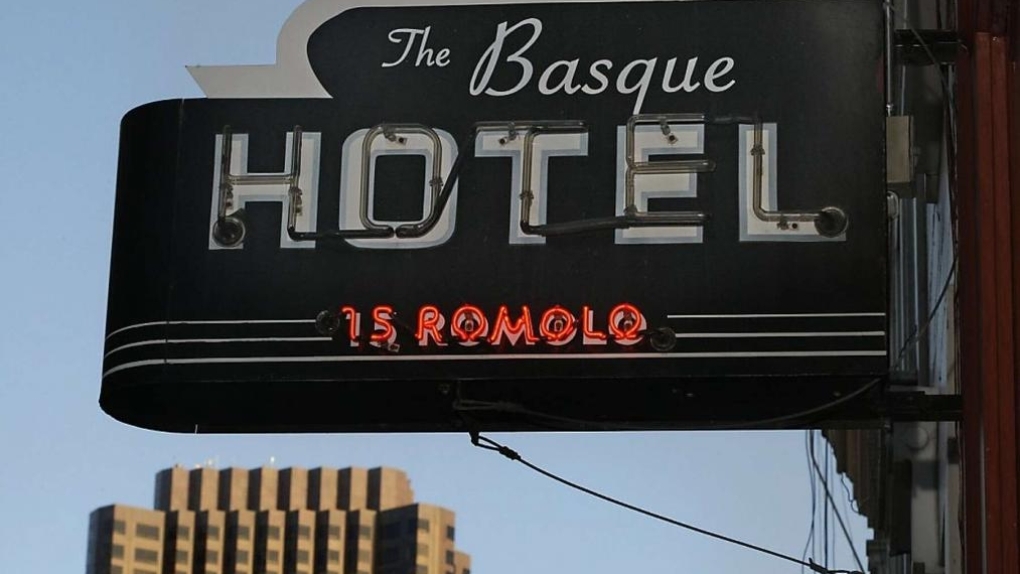

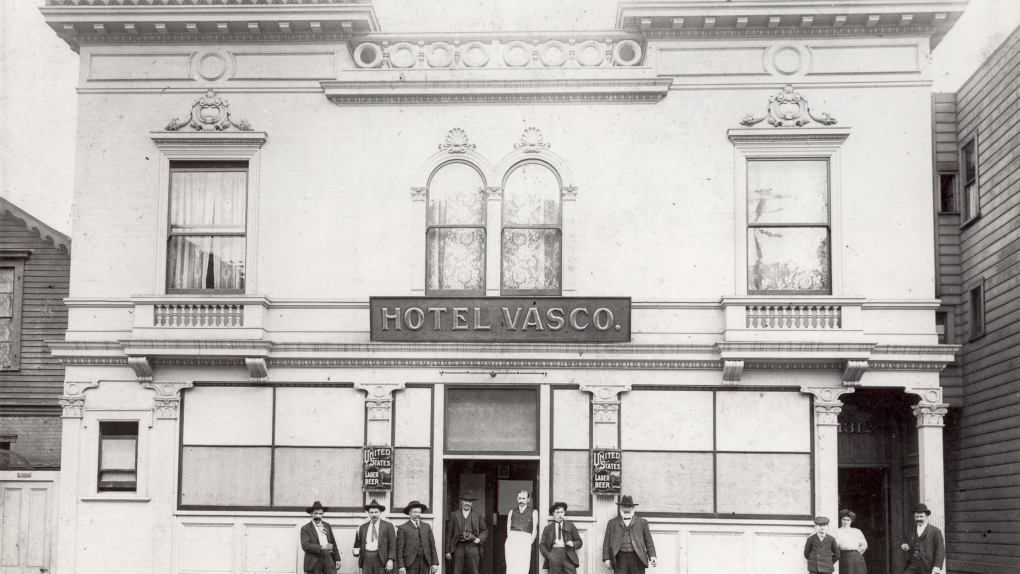

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a Basque could travel across the United States from coast to coast without leaving the support networks that Basque immigrants had begun to establish since the mid-nineteenth century. If they landed in New York, the point of reference was Hotel Santa Lucía, operated by Valentín Aguirre. From there, it was common to undertake long train journeys, relying on a remarkable network of boarding houses or ´Basque hotels,´ which were most concentrated in the states of the American Far West.

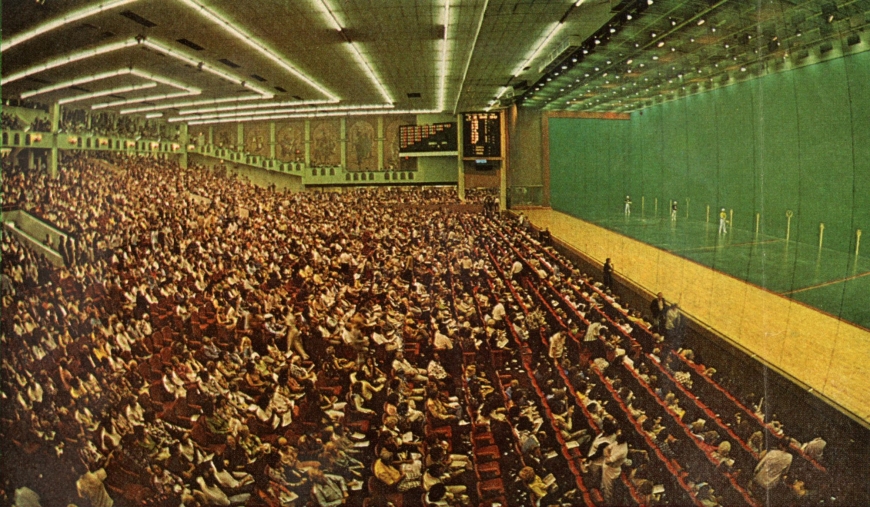

During the pandemic, the most obvious traces of 150 years of Basque immigration to the United States seemed to fade away. In November 2021, the Dania Jai Alai fronton in Florida hosted the final match featuring a professional team of cesta punta ball players, consisting of 28 athletes who had to rebuild their lives. Nine months later, Michael Bordagaray, the last Basque border living in the old style in one of the many Basque hotels opened by Basque immigrants in the second half of the nineteenth century, died in Chino, California.

This winter, however, profesional level cesta punta, or jai alai, which has been enjoying a comeback in the Basque Country in recent years, returned to Florida. The official register of euskal etxeas, or Basque centers, still lists 37 centres from coast to coast. In the coming days, the Basque-American community will celebrate Jaialdi, a major festival held every five years in Boise, Idaho. Jaialdi brings together the heirs of an America of frontons and ikastolas, of gold prospectors, shepherds, hoteliers, pelotaris, exiles, and borders

From 29 July to 3 August, Jaialdi will come alive this year with six days of festivities in Boise that bring together folklore, rural sports exhibitions and concerts by artists from across the Atlantic. Beyond the scheduled programme, what makes this event truly special is its unifying power for a community as unique as the Basque-American communit.

“These celebrations serve as a source of reaffirmation, as the Basque diaspora has been holding festivals or jaialdis since the nineteenth century in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and even Brazil. In 1882, for example, there was a particularly large celebration in Buenos Aires. The Jaialdi in Boise is unique in that it takes place every five years and is so well known and highly visible. It´s like the Sanfermines festivities in Pamplona: there are many festivals, but none are as visible. In the case of Jaialdi, we can also say that it is a very special festival,” explains Xabier Irujo, director of the Basque Studies Center at the University of Nevada in Reno and professor of genocide studies

Boise, the capital of Idaho, is also the capital of Basque immigration in the United States. The city of 240,000 inhabitants is located at the foot of the Rocky Mountains and for 16 years, until 2020, had a Basque-speaking mayor, is home to some 20,000 inhabitants of Basque origin and has an ikastola (Basque school) and a small Basque neighbourhood (the Basque Block).

The map of the Basque centres that still survive in the United States, however, offers a much broader picture: 12 are in the State of California, 7 in Idaho, 5 in Nevada, 2 in Washington State, 2 in Wyoming, 2 in Oregon and 2 in New York, while Virginia, Colorado, Florida, New Mexico and Utah each have one Basque centre.

“The first wave of immigration dates back to the second half of the nineteenth century. At that time, there was an overlap between immigration from the aftermath of the Second Carlist War and the loss of the fueros [laws and privileges that granted specific rights and autonomy]. Basque immigrants also moved to the American West during the gold rush. While a few sought gold themselves, most were employed to supply provisions to the prospectors,” explained Irujo.

Since the late nineteenth century, the immigration of Basque shepherds to the American Far West became a demographic phenomenon that depopulated some Basque valleys and sparked fierce criticism of the recruiters, facilitators and, in many cases, instigators of migratory processes that ultimately proved much harsher than what had been promised.

“Most of the shepherds came from the northern valleys of Navarre, from the areas of Bidasoa or Baztan, and from Lower Navarre, on the other side of the Pyrenees, or from Bizkaia, from towns such as Lekeitio or Gernika. They came to a land that was completely new to them and in most cases only spoke Euskara. Unlike in Uruguay or Argentina, there was no significant Basque presence prior to this, and that is where the Basque hotels emerged. They became reference points for these young people, whose numbers grew to several thousand over the decades,” added Irujo.

Boarding houses arose from Basque immigration itself. And from those lodgings came the game of Basque pelota in the United States. As hotels became centres of reference for the Basque-American community, small pelota courts began to proliferate, adjacent to the hotels.

In 1900, Basque pelota became an Olympic sport at the Paris Games (Spain won its first ever gold medal in this sport), which spurred the expansion of the sport. A year later, the first match recorded in the American press was played at the Eder Jai in San Francisco. And in 1904, the first large fronton was built on the occasion of the Saint Louis World’s Fair in Missouri.

From the 1960s and 70s onwards came the boom of cesta punta, which brought new groups of Basques, although in much smaller numbers.

By then, Basque shepherds had already begun to decline in number, and boarding houses had started to turn into restaurants specialising in Basque cuisine or, quite simply, into Basque centres for immigrants who had made their life in the United States. From offering English classes to immigrants who had just arrived in the United States, they began offering Euskara classes to second- and third-generation Basque Americans.

The Basque presence, however, had already left its mark on Basque-American cuisine, ‘the most authentic regional food in the American West,’ according to H. D. Miller, professor of history at Lipscomb University in Nashville and food critic. And even in the forests of the Far West: scientists from the Universities of Boise and Nevada have documented up to 25,000 arborglyphs carved by Basque shepherds with drawings or inscriptions in Euskara, Spanish or French. It was yet another result of an extremely demanding job that required him to be alone for months, herding flocks of a thousand sheep.

When they came down from the mountains, the Basque-run centres became their points of reference, while the Basque-American community festivals offered them a sense of escape. The Jaialdi in Boise will be the big event for some of them and for many of their descendants. It will also be the big event for some of the 8,000 Basques who have emigrated to the United States in recent years.

In many cases, these are skilled professionals who benefit from much better social and working conditions than the shepherds of the last century, and who engage with the legacy of the Basque centers primarily from a recreational perspective.

Ander Goyoaga is a journalist. He is currently correspondent in the Basque Country for the newspaper La Vanguardia.