New creative talent – driving force behind art, music, literature, theatre and cinema

New creative talent – driving force behind art, music, literature, theatre and cinema

16 Apr 2024

The Basque Country, until recently a region whose image was completely overshadowed by the stigma of violence, seeks to redefine itself to the world through culture. “We have to convince ourselves that culture is what makes us visible in the world,” wrote the poet and novelist Kirmen Uribe. Certainly, the Guggenheim Bilbao museum, the San Sebastian International Film Festival and the work of creators with a universal vision are some of the key elements associated today with the Basque Country abroad. However, the cultural landscape of the Basque Country is much more intricate and is undergoing a remarkable renewal.

Cinema

End of the exodus

According to Joxean Fernández, director of the Basque Film Library, Basque cinema is enjoying a sweet moment now that a number factors that thwarted its development are no longer in play.

“First, the exodus to Madrid in the 1980s and 90s has largely stopped. Our filmmakers typically stay in the Basque Country, even if they film in other locations, and this represents a significant shift. Second, the relationship with the Basque language has changed. Today, Basque is clearly a language of cinema, mostly owing to sociological changes. The generation of Victor Erice, Pedro Olea, Ana Díez and Montxo Armendariz didn’t speak Basque. The second generation – Alex de la Iglesia, Julio Médem, Enrique Urbizu, Daniel Calparsoro, Elena Taberna and Bajo Ulloa – didn’t speak Basque either. However, Basque is the language of many of today´s filmmakers, such as the Moriartis (Joxe Mari Goenaga, Aitor Arregi and Jon Garaño), Asier Altuna, Estibaliz Urresola, Lara Izagirre, Telmo Esnal and many others,” he explains.

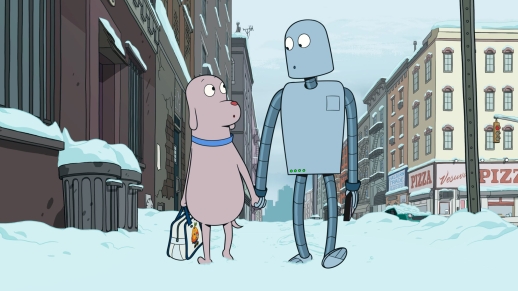

Joxean Fernández also points out that Basque cinema “has expanded both in terms of genre and reach. We see that Isabel Herguera made it to the Official Selection at the San Sebastian Film Festival with her auteur animated film, and on streaming services we have Alex de la Iglesia with ‘30 monedas’ or the Moriartis with ‘Balenciaga’”.

The director of the Basque Film Library cites among the recent milestones in Basque cinema “the premiere of ‘Handia’, a turning point for Basque-language cinema with ten Goya awards, or last year’s recognition of ‘20,000 Species of Bees’ and ‘O Corno’. Seeing Estibaliz Urresola’s film winning the Silver Bear for Best Leading Performance in Berlin and Jaione Camborda taking the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian Film Festival was very important”. Fernández points out that “the inclusion of women is another key feature of this boom, although there is still a long way to go, particularly in fiction. We also need to take more steps to promote Basque-language cinema. Regardless, we’ve seen that Basque cinema is good not just because we say so, but because people outside the Basque Country tell us so.”

According to Fernández, this growth has come about thanks to “talent and courage in creation and production, and also thanks to a series of very well-coordinated institutional policies". In any case, Fernández warns that this is a very competitive sector: “There will be no shortage of challenges.”

Performing arts

Talent unleashed

Regarding the performing arts, Ana López, director of Teatro Barakaldo and a board member of the Basque Theatre Network, Sarea, particularly emphasizes the rise of new talent in both theatre and dance: “Despite the notion that theatre is perpetually in crisis, we’re witnessing an emergence of young talent on stage and a notable increase in the presence of women in the creative arena. María Goiricelaya exemplifies this trend. In dance, we see a similar phenomenon, with compelling artists like Olaia Valle.”

But López sees a problem when it comes to bringing all this talent to the stage: “There’s a disconnect between the amount of new talent and the capacity of venues to accommodate it. This gap is much more evident in the case of dance. Sometimes the aim is to fill the theatres with well-known faces from abroad, despite the fact that we have local talent of equal or even greater caliber. In any case, we’re pleased to see the emergence of new talent that will give us with much to talk about, and we highlight the contribution of Dantzerti, the higher school of dramatic art and dance.”

Literature

Writing across generations

Karmele Jaio, one of the most highly recognised writers on the Basque literary scene, identifies four dynamics that place Basque literature at an “important moment in terms of creation”. The first is generational and particularly affects literature in Basque: “Several generations coexist, relate to each other and write at the same time, which is enriching,” she explains. In other words, the generation of Anjel Lertxundi, Bernardo Atxaga or Arantxa Urretabizkaia has not passed on the baton, but shares its privileged place on the literary scene with other generations of writers.

Secondly, Jaio highlights “the greater presence of women writers”, a trend that is particularly evident in the latest editions of the Euskadi Literature Awards – the most important recognition in the Basque literary panorama – which, in 2022, honoured seven women writers across its seven categories. Authors such as Eider Rodríguez, Edurne Portela, Uxua Apaolaza, Txani Rodríguez, Aixa de la Cruz, Uxue Aberdi, Irati Jiménez and Karmele Jaio herself have become major references in Basque literature, both in Basque and in Spanish.

Jaio points out a third characteristic related to the increasing presence of women writers. “This trend has facilitated a shift in themes and, most importantly, perspectives, resulting in greater diversity.” Finally, in the opinion of the Vitoria-born author, Basque literature has gained greater visibility. “For years it seemed like Basque literature, particularly literature written in Euskara, was limited to Atxaga or Kirmen Uribe, much like what happened with Galician literature, which was associated only with Rivas. Now, we’re seeing a significant increase in interest from publishers, who are publishing and translating more works by us,” she explains. Karmele Jaio herself has been translated into a dozen languages.

Similar to written literature, bertsolarism (Basque improvisational poetry) also reflects this generational shift, with a diversification of themes and an increasing presence of women. Also significant is the increasing urban influence and the vibrant response from audiences at major events that draw thousands of attendees.

Music

The rise of new soundscapes

When it comes to music, particularly popular music, the Basque music scene is experiencing a nascent transformation that has become especially evident since the pandemic. The dominance of rock, punk, and metal, which significantly shaped the Basque music scene in the eighties and nineties, has transitioned into a broader range of genres fueled by a generational shift.

The tip of the Basque music scene is represented by bands like Zetak, Izaro, Bulego, and ETS, who will take the stage at the Bilbao Exhibition Centre for three days next year, drawing large crowds. However, in recent years, a wave of groups has emerged within the underground scene, contributing to an intriguing and eclectic musical landscape, from the ferocious pop-rock of Merina Gris to the urban styles of Hofe and Bengo, among others.

“Basque music, including songs in Euskara, is fully part of the global stage, resonating with current trends. It has undergone a renewal, resulting in a captivating landscape filled with genuine and authentic musical offerings,” explains Maialen Goirizelaia, professor of Audiovisual Communication at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU).

Regarding classical music, Patrick Alfaya, the director of the San Sebastian Musical Fortnight, believes that the Basque Country is experiencing a phase of “expectant stability”, aiming to renew its audiences. He emphasizes the importance of leveraging strengths such as investments in training that should lead to the development of specific artistic initiatives, as well as promoting an attractive and high-quality choral movement. In the field of classical music, moreover, the two Basque symphony orchestras deserve particular attention: the Basque National Orchestra and the BOS (Bilbao Orkestra Sinfonikoa).

Art

From the Guggenheim to Azala

In the plastic and visual arts, it is important to consider the ‘constellation’ consisting of the Guggenheim Bilbao, the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, Artium, Chillida Leku, the San Telmo Museum, and Tabakalera. However, Beatriz Hérraez, director of Artium, emphasizes the need to acknowledge “other essential spaces, albeit on a different scale, as well as independent galleries and projects like Dinamoa, Azala, kinu/Atoi, Zas, Okela, and bulegoa z/b.”

Hérraez also emphasizes the initiatives of artists featured in exhibitions at Artium in recent years, including Esther Ferrer, Ibon Aranberri, Itziar Okariz, Juan Luis Moraza, Txaro Arrazola, Gema Intxausti, June Crespo, Xabier Salaberria, Erlea Maneros Zabala, Sahatsa Jauregi, Nerea Lekuona and Josu Bilbao. “I’ve left out many names, although I would also mention the generation of female artists who work with film and the moving image: Laida Lertxundi, Ainara Elgoibar, Maddi Barber, Irati Gorostidi, Marina Lameiro and Mirari Echavarri, among others.”. For this reason, Hérraez considers that Basque art is experiencing “an excellent moment”.

This diagnosis could potentially apply to most sectors, despite the risk of becoming complacent. It encourages us to reassess the cultural references established in the Basque Country, as new generations are now stepping up.