In the early twentieth century, particularly in the transitional years between the 1910s and 1920s, the visual arts in the Basque Country reached remarkable levels of quality. The wealth generated by industrialisation in and around Bilbao led to the establishment of an unprecedented art system, including artists´ groups, art criticism, and the founding of museums. This marked a blossoming of art in a country that had previously lacked both artists and a culture of art collecting.

The Fabric of Basque Art

17 Jul 2025

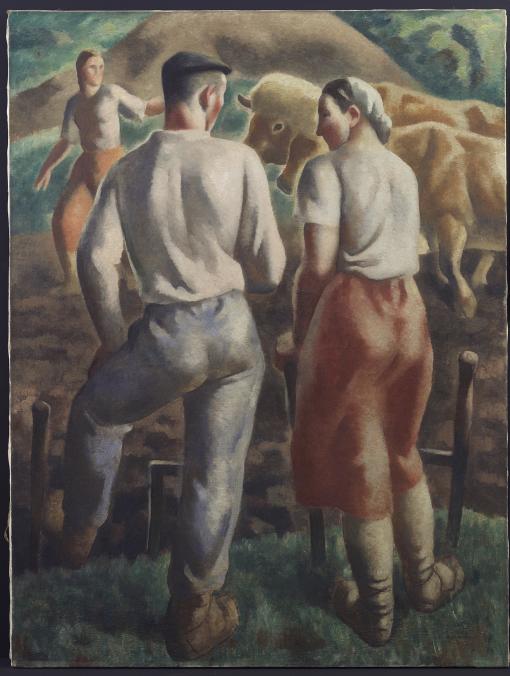

The creators organised within the Association of Basque Artists, drawing primarily on the ideology of Noucentisme – an artistic movement that aimed to combine tradition, modernity and attention to the local – developed an original artistic language. Following in the footsteps of Adolfo Guiard, Darío de Regoyos, Francisco Iturrino and Ignacio Zuloaga, who introduced the latest trends in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism from Paris during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, these artists were sceptical of the radicalism of the avant-garde. Artists such as Aurelio Arteta, the Zubiaurre brothers, Juan de Echevarría, and Antonio de Guezala created a distinctive form of modernity that was primarily pictorial.

During those years, the existence of ´Basque art´ was debated, sometimes in relation to the rise of nationalism and other times in the context of modernity. Some critics noted its distinctive features. The first and most important attempt at a synthesis in this respect was, without a doubt, Juan de la Encina’s ´La Trama del Arte Vasco´ (1919). His book established the canon and historiography of Basque art for the following decades, despite the critic´s earlier questioning of it.

In the 1930s, San Sebastián replaced Bilbao as the centre of the art world with the emergence of young creators such as Jorge Oteiza, Nicolás de Lekuona, and José Manuel Aizpurua. However, the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 thwarted the development of an environment that favoured modernity in the arts and architecture. In the darkness of the post-war years, a sense of renewal emerged from abroad, particularly with Oteiza´s return from South America in 1948. At the beginning of the 1950s, the construction of the Arantzazu basilica, despite resistance from ecclesiastical authorities, served as a catalyst for the renewal of art in the Basque Country and its full integration into avant-garde trends.

Against this backdrop, artists such as painter María Paz Jiménez and sculptors Jorge Oteiza and Eduardo Chillida made a firm commitment to abstraction. In 1957, Oteiza gained international recognition at the São Paulo Biennial. After achieving his experimental goals, he left sculptural practice to focus on theorising and promoting various popular initiatives. At the same time, Chillida achieved great success in Europe and America, especially after his triumph at the 1958 Venice Biennale. Initially utilising a militant approach to geometry and later embracing a more evident dramatism aligned with the influence of informalism prevailing in Paris, Basque art achieved previously unthinkable results.

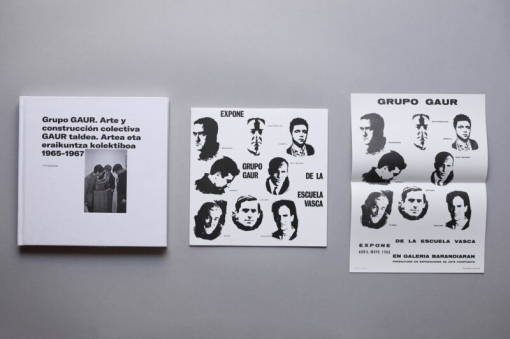

In 1966, the Gaur group was formed in Gipuzkoa with the aim of reviving Basque culture and identity amidst the suffocating repression of the Franco dictatorship. Gaur, which means ‘today’ in Basque, was made up of Jorge Oteiza, Eduardo Chillida, Remigio Mendiburu, José Antonio Sistiaga, José Luis Zumeta, Amable Arias and Néstor Basterretxea. Its aim was to define the Basque School of Contemporary Art, which led to the emergence of the two other groups: Emen (‘here’) in Bizkaia, whose greatest exponent is the political art of Agustín Ibarrola, and Orain (‘now’) in Álava. Although the groups did not last over time due to disputes among the artists, they established the foundations for protest art and identity art that expressed a Basque ´soul´ through new contemporary avant-garde languages. This movement ultimately created a universe that resonated with popular culture using a radically visual language: abstraction as a representation of the people.

During the heyday of Basque art, a new group of creators confronted the metaphysical and mythologising aesthetic of their predecessors; some, like Esther Ferrer, through conceptual and performative approach; others, more turned more to pop culture and an acid, surrealist figuration, such as Mari Puri Herrero, Vicente Ameztoy and Andrés Nagel.

The 1970s saw the development of a wide range of artistic movements. The political transition to democracy and the establishment of autonomous institutions was accompanied by a new generation trained in the recently created Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of the Basque Country. This allowed for the continuation of figurative languages – with artists such as Jesús Mari Lazkano – as well as abstract ones. Among the latter is a group of creators concerned with the meta-artistic dimension of their research, both in painting, with Darío Urzay as the main exponent, and in sculpture. Building on the ideas of Jorge Oteiza and post-minimalism, Ángel Bados, Txomin Badiola, Marisa Fernández, Juan Luis Moraza, and Elena Mendizabal formed the primary response to the crisis of modernity, known as New Basque Sculpture. Influenced by postmodernity, this movement fostered shared interests and common formalist and theoretical languages, defining a new approach to understanding Basque art in the 1980s.

The artists who began working in the 1990s, trained at the Arteleku production centre in Donostia, brought various innovations to the table. With New York as a point of reference, the dissolution of traditional disciplines, along with identity, the body and social and political issues, became subjects of debate for a generation in which women gained increasing visibility. Miren Arenzana, Itziar Okariz, Sergio Prego, Ana Laura Aláez and Jon Mikel Euba developed their work in line with globalisation and opened the door to a group of creators trained in different international fields coinciding with the opening of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. In the era of installation and diverse languages, various artists navigate the local and global realms, employing a historicist revision of tradition and embracing a broader conception of art. Notable among them are Ibon Aranberri, Maider López, Asier Mendizabal, and Abigail Lazkoz

Compared to the more defined notions of ‘Basque art’ experienced a hundred years ago and again fifty years ago, the current concept exhibits distinct characteristics that reflect increasingly varied references and greater hybridisation. Within a framework of established institutions – such as the Faculty of Fine Arts, museums, art centres, and galleries – and a strong network of independent projects like Consonni, Bulegoa z/b, Okela, and Tractora Koop, a rich artistic fabric of multiple threads has been woven. Dani Llaría, Damaris Pan, Mar de Dios, and Nora Aurrekoetxea provide fresh perspectives while questioning and defining our identity in an increasingly complex and changing world.

Mikel Onandia is an art historian and exhibition curator. His research focuses on modern and contemporary art and art collecting.