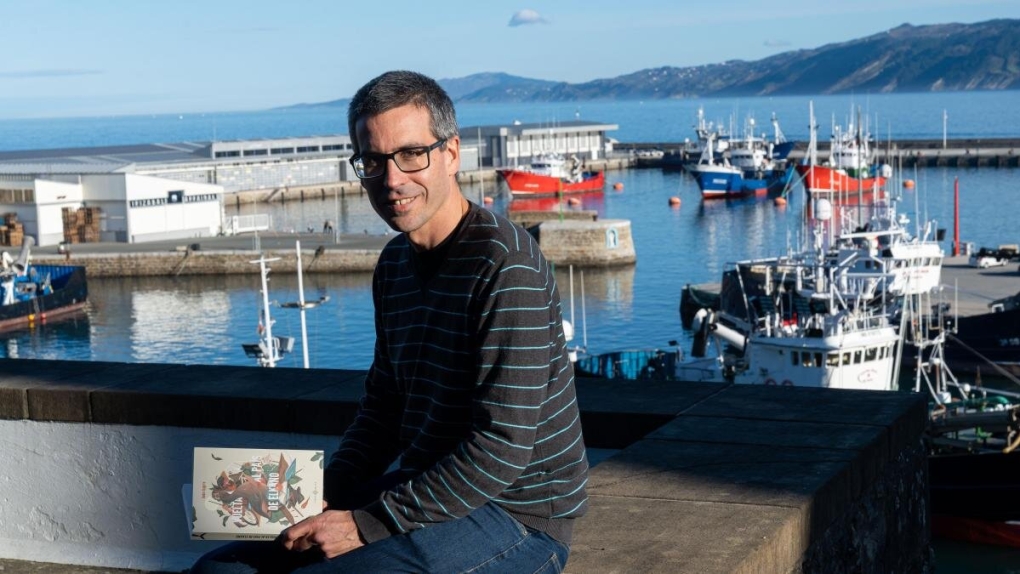

In ´Vuelta al país de Elkano´ (2022), author and journalist Ander Izagirre challenges the perception of Basques as a people confined to the farmhouse.

A land of ‘contrast and sailors’: the other history of the Basque Country

12 Jun 2023

The land of the Basques has been more a people of ‘contrast and sailors’ than ‘isolated peasants’, a people as worthy of admiration on some occasions as a source of terror on others. This evocative idea permeates the pages of Ander Izagirre´s latest book, ´Vuelta al país de Elkano´ (Libros del K.O.). His work confronts the myth of the Basques as a people who never ventured far from the farm. It is a story of a journey through a small territory, with the occasional foray to the Moluccas and Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. The book represents a rediscovery, drawing lessons to address the new global challenges.

The Elkano Foundation in the Basque Country responsible for organising events related to the 500th anniversary of the first circumnavigation of the world by the sailor Juan Sebastián Elcano from Getaria commissioned the creation of this work. Acclaimed journalist and author, Ander Izagirre, winner of Poland´s Ryszard Kapuscinski Award, saw the book as a journey to rediscover a territory he thought he knew well and which he now sees with different eyes. Elcano´s voyage is the common thread. The result is a tale of whale hunters, privateers, Cagots, French-Basque Jews, African-Basque fishermen, enterprising indianos (immigrants who made their fortunes in the Americas and returned), and intrepid surfers. A land that has gazed outward for centuries, blending and borrowing language and culture, accustomed to interaction and pidgin.

The journalist from San Sebastian argues that the enduring myth of a pastoral, isolated, and ´increasingly obsolete´ Basque Country was sustained because it failed to recognise the crucial role of the sea in shaping its identity. ‘Basque maritime history involves amazing adventures, as well as bloody incidents and conquests. The sea is unpredictable, and it appears that at one point, it was simpler to depict a community with its wholesome traditions before the arrival of outsiders," he says.

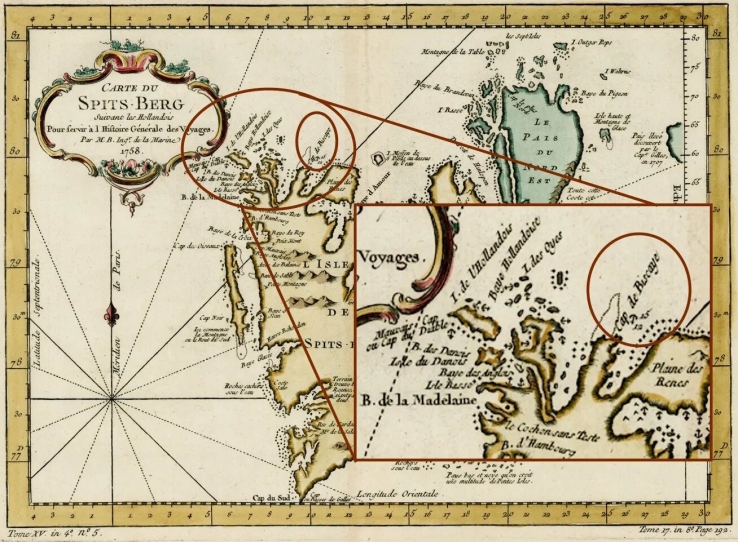

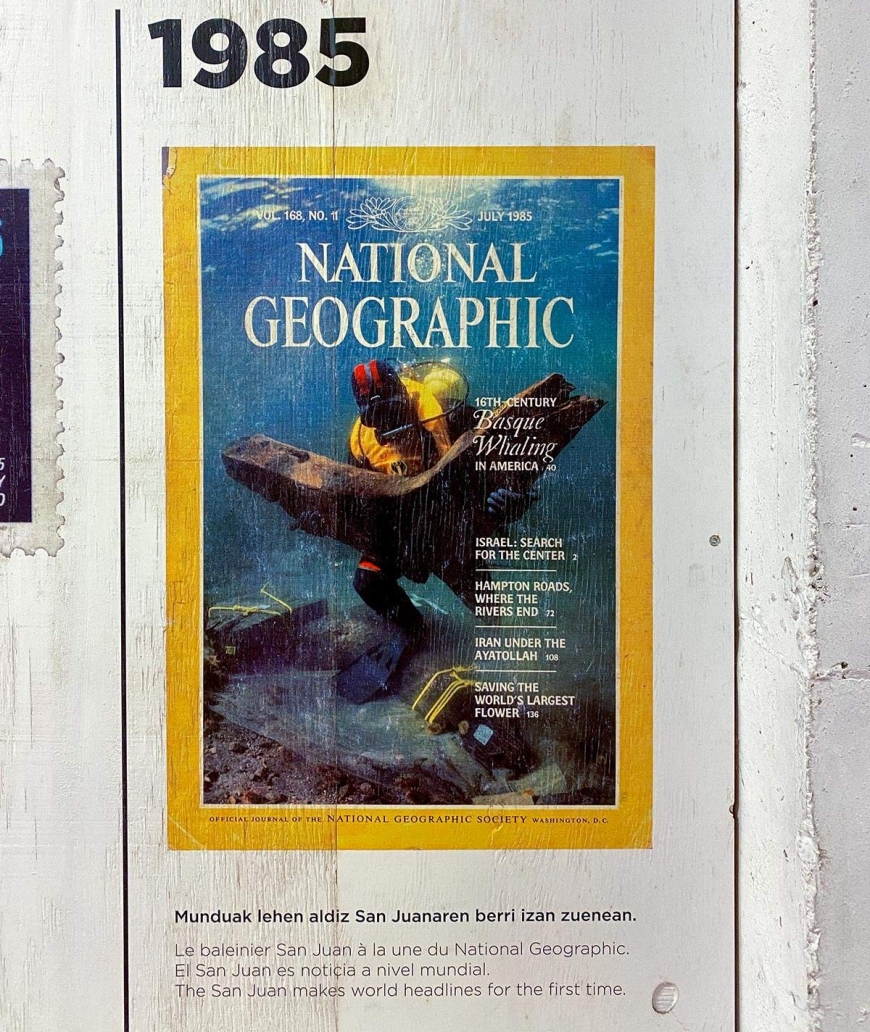

The truth is that this other story of the Basque world, the one that looks seaward, is much more interesting and evocative, with the whale as one of its most emblematic features. ´The whale country,´ as Izagirre depicts it, persisted, even though the influence of whale hunting on the Basque ports and its pivotal role in driving the economy had been largely overlooked for decades. Although whales were depicted on the coats of arms of numerous coastal towns, it was only through the efforts of an Anglo-Canadian historian, Selma Huxley, and a National Geographic article that their memory was rekindled.

‘The whale represented a way of life and not only fuelled the economy along the coast but also gave rise to secondary industries in the interior. When they wiped out the whales here, let´s be honest, they went looking for them all across the Atlantic,’ he explains. From these forays came such peculiar things as the Basque-Icelandic pidgin, reflected in a 745-word glossary that still exists today, or the Basque-Algonquian pidgin, a simplified mix of Basque with words from the languages spoken by the native tribes of Canada.

‘Today we inhabit landscapes and admire postcards that we no longer understand,’ says Izagirre. ‘We take selfies on San Juan de Gaztelugatxe – famous for its role in Game of Thrones – but we don´t understand its historical significance in preventing ships from getting lost. It looks like it was designed for a photo op, but it meant the difference between life and death,’ he adds.

The farmhouse, an ancestral treasure trove, is another product of the seafaring and travelling history.

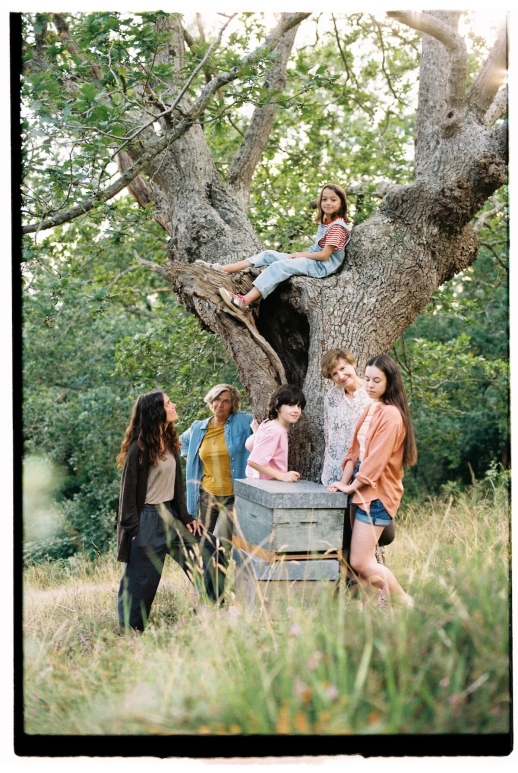

The writer from San Sebastian makes no concessions to essentialism, embarking on a journey to rediscover every corner. ‘The farmhouse – an iconic feature of the landscape, an ancestral treasure trove and symbol of identity – is another product of the seafaring, travelling and multifarious history of the Basques,’ he points out. In many cases, farmhouses were ‘gigantic apple-pressing machines used to supply cider to a fleet that expanded as it began to travel to America: a machine they would live in.’

Sailors, writers, historians and chefs accompany Izagirre on his journey to rediscover the Basquelands. Archaeologist Mertxe Urteaga, expert on the Romanisation of the Basque territory, helps Izagirre debunk another myth – Asterix, the story of an unconquerable people who resisted every imperial expansion. ‘In fact, the Basques became integrated into the Roman domain and experienced a transformation that made them stronger, Izagirre points out. The language brought by those Romans would be forever engraved in a large part of the Basque lexicon.

A compilation of stories and adventures, the book outlines two key contexts of globalisation: one linked to the expansion of Rome and the other to the rise of sailing in the sixteenth century. But the author also looks to the twenty-first century, to a new age of globalisation, and tries to draw lessons from it.

Izagirre asks himself what a Basque person is like today. And he finds the answer in the Arctic, following the trail of some scientific tweets from there in Basque. The author is Naima El Bani Altuna, a paleocenographer, sedimentologist and geologist who studies historical ocean warming. Her father is from Casablanca and her mother from Bergara. On one of her expeditions to the Arctic, her companions were ‘nonplussed’ at seeing how excited she became when they passed by Biscayarhalvøya, the ´peninsula of the Vizcainos´, and Biscayarfonna, the ´glacier of the Vizcainos´. Vestiges of the whaling past. In his book, Izagirre writes how surprising it was to imagine Basque whalers settling on that coast, and the remarkable journey they made in their wooden boats.

He finds more answers with Moussa Thior in the port of Ondarroa. The Senegalese fisherman and former wrestling champion speaks proudly about the level of integration they have achieved in the village. ‘The important thing is to get to know people to strip away prejudices. That´s the good thing about Ondarroa. It´s a small town, everyone knows each other, and if someone does something wrong, they don´t blame the whole community" Izagirre explains. ‘The first arrantzale (fisherman), whose full name we know is Cayo Julio Níger, was a young black man from Bidasoa, a descendant of slaves. We come from a world that is more global than we think and it would be a mistake to build walls today.’

Ander Izagirre also senses another danger: complacency. In the town square of Zarautz, where oxen used to haul the galleons, you can now see surfers riding the waves half a century after the sport first came to Europe via the Côte des Basques in Biarritz: ‘Waves used to be a curse, now they´re a blessing. It’s wonderful to have reached this point. I´m optimistic, I see a vibrant and largely open society, but there´s a risk of stagnation, as well as the potential danger of isolating ourselves.’