The flag of this French overseas territory off the south coast of Newfoundland pays homage to the Basques, Bretons and Normans who arrived at least as far back as least the sixteenth century. This tiny archipelago was key to the development of cod fisheries and, in the twentieth century, to smuggling alcohol.

Saint Pierre and Miquelon: a Basque flag in a North Atlantic archipelago?

01 Mar 2024

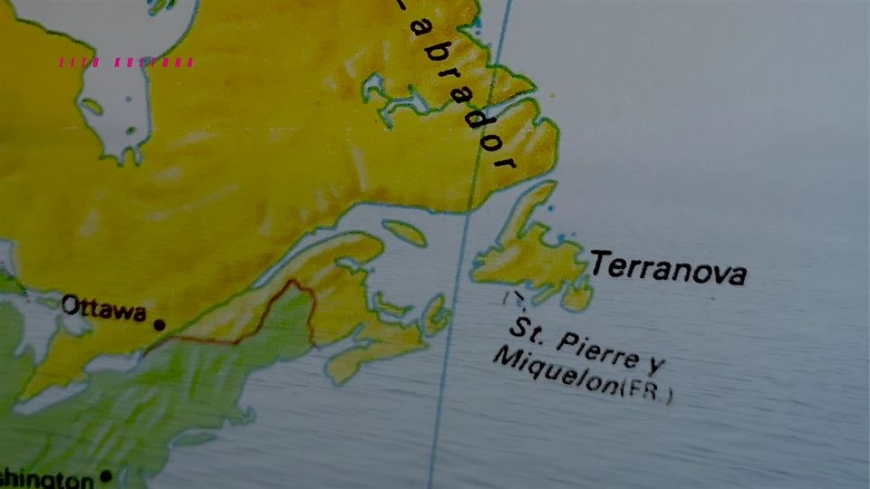

More than 2,500 miles from the Basque coast and 25 kilometres south of Newfoundland lies a tiny archipelago with several frontons, an ikurriña on its colourful flag, and an annual Basque festival. These anecdotal details highlight a Basque presence in the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon that extends beyond mere anecdotes. Similar to other episodes linked to the maritime culture of the Basque coast, this presence has garnered significant interest in recent years. Although located off the Canadian coast, Saint Pierre and Miquelon (also known as Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon or San Pedro y Miquelon) is officially a ‘territorial overseas collectivity’ belonging to France. It has a population of about 6,000 and covers only 240 square kilometres of land divided between the islands of Saint Pierre, Miquelon and Langlade, together with some smaller uninhabited islands.

Strategic location: A site of clashes between France and England, Al Capone visited to oversee his smuggling network

Its peculiar flag, a modern creation that has also been used as a coat of arms, has gained significant visibility in the Basque region in recent years, owing largely to something seemingly mundane: it is one of the 270 flags featured on WhatsApp or Twitter emojis.

Anecdotes like this, however, to draw attention at a local level to the territory´s maritime past, a story that contrasts, in the opinion of Xabier Alberdi, historian and director of the Basque Maritime Museum in San Sebastián, with ´the idea of a past that speaks of an isolated Basqueland hidden away in the mountains and villages´. ´That picture has nothing to do with reality,´ he says.

Cartier and the arrival of fishermen

Indeed, the colourful insignia of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, displayed on public buildings but not fully official, speaks volumes about the archipelago´s history.

On one side is a gilded vessel representing the Grande Hermine, the ship that brought Jacques Cartier to the island of Saint Pierre on 15 June 1535. On the left, the Basque, Breton and Norman flags reflect the origins of most of the island´s inhabitants, although it should be noted that the islands have been inhabited since prehistoric times, with traces of Inuit culture discovered in the region.

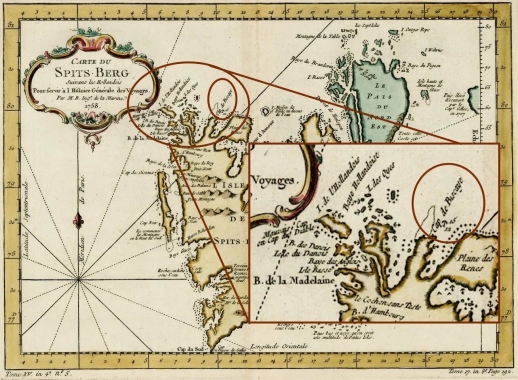

The presence of Basque fishermen on the island dates back to at least the beginning of the sixteenth century, according to Xabier Alberdi: ‘Very early on, the area became integrated into the fisheries that flourished in this part of the Atlantic. The first documented references date back to the beginning of the sixteenth century. Sometimes the specific ports they visited are not mentioned, and Newfoundland is referenced in a general manner, encompassing not only the island itself but also extending to include Saint Pierre and Miquelon, along with other continental areas such as the Labrador Peninsula and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence´.

Alberdi considers it ´feasible´ that the Basque fishermen arrived even before the sixteenth century, while pointing out that the currently available documents do not allow for dating this occurrence any earlier. ´We may know more about this in the future. Not all the documents that could provide insights have been thoroughly reviewed, and the ongoing developments in archaeology in Canada might very well yield results. What we do know from archaeological evidence is that there was a Viking presence in northern Newfoundland and we also know of the existence of expeditions of settlers from Greenland,´ he explains.

450-year relationship

Beyond those initial forays into the archipelago, what is most remarkable is that the Basque presence on the islands endured for over 450 years. Throughout this period, these fishermen coexisted amidst numerous military conflicts between France and England vying for control of the territory.

´The first incursions by Basque fishermen, as well as those from other territories, were seasonal. No stable European settlements were established. The fishermen would arrive in late spring, engage in their fishing activities, and depart before summer. Starting in the early seventeenth century, however, Nouvelle France began to organise its imperial framework, leading to the establishment of stable colonies. Among these first settlers were French Basque fishermen from Saint-Jean-de-Luz or Ziburu, and Guipuzcoans who took part in the expeditions. They settled, fished and sold the catch to the ships coming from Europe. This gradually strengthened the relationship’, explains Alberdi.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the expeditions of cod fishing vessels from Biscay and Guipuzcoa gained momentum. The Basque presence in these islands – and in the whole Newfoundland area – continued until the beginning of the 1980s, when cod fishing in the region began to decline.

‘We’re not talking about a one-off relationship, but a centuries-old and centuries-long contact. Why? The immense wealth of fisheries in the area. The cod that Europeans fished throughout this area fed an important part of the continent and had an immense economic impact,’ he adds.

Unlike other areas of the Atlantic, the Basque presence in Saint Pierre and Miquelon was linked to cod fishing, not whaling. ‘This doesn´t mean that they wouldn’t catch whales if they had the chance.’ However, as Alberdi points out, ‘Saint Pierre and Miquelon was not a whaling station like other sites along the Canadian or Icelandic coast.’

Al Capone´s suite

The enduring Basque presence in the islands today is a result of this centuries-old presence. The Rue des Basques in Saint-Pierre is one of the many place names that recall this close transoceanic connection. The street runs from the port to a few metres from Hotel Robert, where Al Capone stayed in a suite during the Prohibition era in the 1920s.

The archipelago experienced a golden age as a result of the alcohol ban on U.S. soil. During a period of decline following World War I, in which many of the islands´ fishermen fought, the bootlegging trade became the economic engine of the islands´ economy.

Extraordinary shipments of rum, whisky and champagne from across the Atlantic arrived in the ports of Saint Pierre and Miquelon. Once there, they were transferred to smaller fishing boats and taken to U.S. shores.

A few years ago, Piper-Heidsieck released a limited edition of Prohibition Champagne, commemorating the Prohibition era. The label featured a black and white photo of the port of Saint Pierre, a sign of its key role in the bootlegging trade. Al Capone visited the Hotel Robert to witness first-hand the operations of his extensive smuggling network.

The islands today

Fishing has seen a steady decline in recent years, due in large part to decades of overfishing until the 1980s. This led to strict fishing bans. Consequently, the archipelago has seen its population decrease over the past decade. However, there has also been a notable rise in nature tourism, capitalising on the diverse historical experiences of the region.

This captivating story is rich with references to its Basque, Breton, and Norman settlers, as well as the celebration of Basque festivals held in August, and Saint Pierre and Miquelon’s strategic significance for Nouvelle France, colonial England, and more recently, alcohol smuggling in the twentieth century.