The death of the last resident of a boarding house established by Basque immigrants marks the end of a chapter whose roots go back to the mid-nineteenth century.

The last room at the Basque hotel in the American West

05 Nov 2022

The history of Basque immigration to the U.S. ended one of its most curious chapters this summer. In August, the last Basque boarder passed away. Michel Bordagaray was the last resident to live in the manner of times past at one of the numerous hotels set up by Basque immigrants in the latter half of the nineteenth century. These boarding houses offered refuge and support to the thousands of shepherds who crossed the Atlantic. He was the final link to an institution deeply rooted in states such as Idaho, Nevada, California, and Oregon, and which now operate as restaurants, attracting customers with the promise of ´Basque family style dining´.

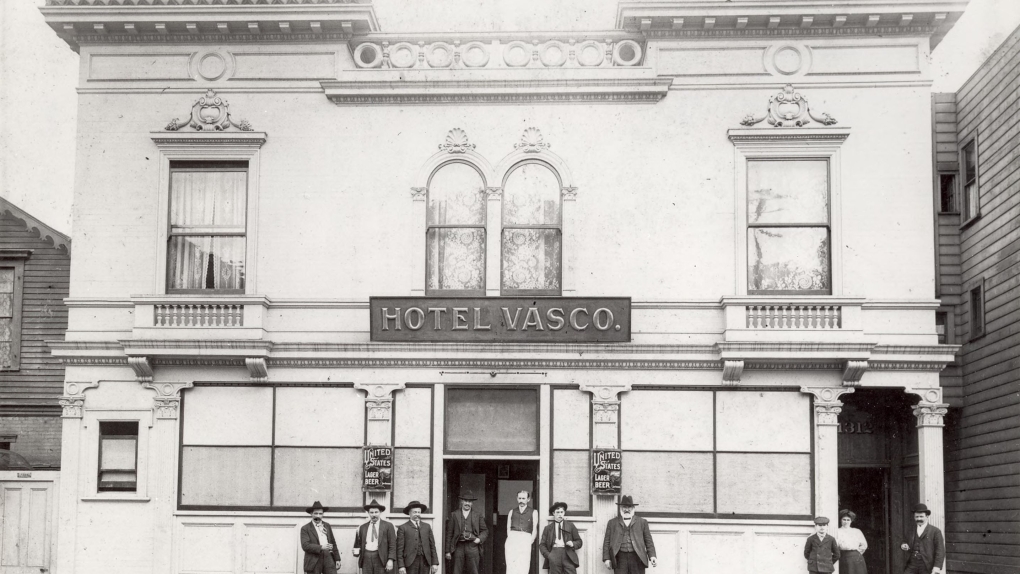

The history of these establishments, known as ostatus among Basque immigrants and Basque hotels or boarding houses by the locals, stretches back over 150 years. The institution of the Basque hotel, however, went through different phases, ultimately becoming hotels specialising in Basque cuisine, or Basque centres (euskal etxeak) – with or without dining facilities – focused on promoting Basque culture on the other side of the Atlantic.

The hotels were run by Basques, and their only customers were Basques from the Old Country.

Historian Xabier Irujo is a professor at the University of Nevada, Reno, director of the University´s Center for Basque Studies, and a leading expert on this phenomenon. “Basque hotels are associated with the immigration that occurred from the second half of the nineteenth century onward. Two phenomena overlapped: firstly, immigration linked to the aftermath of the Second Carlist War and the loss of historical rights, known as fueros, and, secondly, the gold rush. A few Basques went in search of gold, but the majority worked to supply provisions – food, milk or wool – for the gold diggers. Basque immigration linked to shepherding and livestock would be transformed from that time onwards, especially during the twentieth century," he points out.

The Basque hotels emerged from the necessities of young Basque immigrants who had barely reached puberty. "When they arrived at the end of the nineteenth century, there was no substantial Basque presence akin to that in Uruguay or Argentina. They landed in a place that was completely foreign and, coming from the Baztan Valley in Navarra, the area around Lekeitio and Gernika or the French Basque region of Basse-Navarre, most of them could only speak Basque. Therefore, the hotels become centres of reference for these young people, who over the decades numbered several thousand," Irujo explains.

Some of the most iconic boarding houses flourished from the 1960s onward, hotels operated by Basques, catering exclusively to migrants from the Basque territory. Over the years, the gears of this hospitality network were honed, ultimately spanning the entire United States from coast to coast.

“There was a point when young people were recruited through what were referred to as enganchadores, or ´hookers´. Much criticised in Basque literature, these immigration agents would sell the men on promises of getting rich. The most common way for the young Basques to make their way to New York was by sea from Bordeaux. Valentín Aguirre´s boarding house in Manhattan was particularly important. People would come to the door and shout: "Badira euskaldunak hemen?" (Are there Basques here?). The Santa Lucia Hotel in New York was the first stop,” Irujo says.

From there, the new arrivals would travel by train for several weeks until reaching their destination, where another Basque had hired them to work as shepherds, a job which most of them knew nothing about: "If they did know about shepherding, it was on a much smaller scale. In the United States, the herds numbered 700 or sometimes over a thousand sheep.

It was a very simple job, but extremely monotonous and lonely. The most difficult challenge they had to face was solitude," says Irujo. In his book ´Speaking Through the Aspens´, historian Joxe Mallea-Olaetxea delves into the profound solitude experienced by those shepherds, highlighting the lasting impact they left on the bark of countless trees that still bear drawings, dates, initials, and images of women. "The shepherds spent months completely alone, with two dogs, a donkey and up to 1,500 sheep," Mallea-Olaetxea points out in the documentary ´Basque Hotel´.

Basque hotels also adapted their facilities to the needs of those shepherds. "They were places they could trust, places of reference. Moreover, there was Basque food, they could speak Basque – which meant they could have conversations –enjoy a game of mus, listen to music or play Basque pelota. They could also receive mail and assistance with loans. All the boarding houses I know of functioned as cooperatives, not as private holdings, and mutual-aid societies were set up, a kind of social security system that could cover costs in the event of an accident. They even served as small hospitals for the shepherds," says Irujo.

As time went by, the situation of those first Basque immigrants also changed. Most of them overcame the extreme loneliness of shepherding and succeeded in advancing socially. They also managed to shake off the stigma attached to immigration, having been called derogatory terms such as Black Basques or coyotes.

Some returned to the Basque region of Europe, but most remained in the United States. Some even achieved notable economic and political influence in the American West. Paul Laxalt, Governor of Nevada and U.S. Senator; Pete Cenarrusa, former Secretary of State of Idaho; and Dave Bieter, mayor of Boise, Idaho for 16 years, are children or grandchildren of that immigration.

The original purpose of the Basque boarding houses was also changing, as reflected in the doctoral thesis of Basque-American historian Jeri Echeverria. Beginning in the mid-twentieth century, the hotels gradually transitioned away from their role as lodgings and evolved into restaurants specialising in Basque food, or directly into Basque centres, like those that began to proliferate a century earlier in Argentina and Uruguay. In numerous instances, they shifted from providing English classes for newly arrived Basque immigrants to offering Basque lessons for second-generation Basque-Americans.

Gastronomically speaking, the influence would be notable, to the point that Basque-American food has now become "the most authentic regional food" of a part of the American West, according to H. D. Miller, professor of history at Lipscomb University in Nashville and food critic: "The Basque restaurants that have survived, many of them more than a century in business, is that they offer the most authentic regional cuisine found in the western U.S. – part Basque and part chuckwagon, all western."

The pandemic saw the demise of iconic boarding houses such as the Noriega in Bakersfield or the Santa Fe in Reno, both of which had already been operating as restaurants. For years the Centro Basco in Chino, California, was the only boarding house to still have a resident.

The owner, Monique Berterretche, died in February, as did Michel Bordagaray this past summer. Bordagaray had immigrated from Anhauce, Basse-Navarre, France, in the 1960s and spent several years as a shepherd. "When I first came to the Centro Basco, I felt like I was in back in the Basque region. Now, there are fewer and fewer people," he told a Californian media outlet a few months before he passed away.

His passing marked the end of a way of life that, despite decades of decline, persisted for a century and a half. Now, only embers remain. The North American West boasts one of the highest concentrations of Basque centres, especially in the states of Idaho and Nevada. And former Basque hotels like the Star Hotel in Elko and the J T Basque Bar & Dining Room in Gardnerville continue to serve Basque food to visitors.