Born in the same year, both are essential figures in Basque culture, each charting a distinct path. Under the long shadow of Jorge Oteiza, we freely reconstruct the story of these two figures.

100 years of Basterretxea and Chillida: avant-garde and commitment at the pinnacle of art

10 May 2024The relationship between Néstor Basterretxea (Bermeo, 1924-2014) and Eduardo Chillida (Donostia, 1924-2002) was not particularly close, although their paths did cross on more than one occasion. Throughout this exploration we will outline the similarities and differences between two creators who significantly enriched the latter half of the twentieth century with their artistic brilliance. Most importantly, we will delve into the profiles of these individuals, shedding light on their remarkable contributions.

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Basterretxea and Chillida, a myriad of activities, including exhibitions, books, music, cinema, and conferences, will be held throughout 2024 in the Basque Country and beyond our borders. Various institutions and organisations have joined forces to draw up an extensive programme across several cities. It is a wonderful opportunity to revisit – or introduce for the first time – the work of two pivotal figures who immersed themselves in the roots of Basque culture and inspired an avant-garde artistic movement.

First, a sculptural promenade

Can the works of the three giants of twentieth-century Basque art all be found in the same place? Yes, in Donostia, along the urban seaside promenade that starts at the base of Mount Ulia, crosses Zurriola beach, continues along the Paseo Nuevo and culminates at the far end of La Concha Bay, where Eduardo Chillida embedded three sculptures that have since become iconic symbols of the city. Peine del Viento (Wind Comb) was not the favourite piece of the creator and sculptor from San Sebastian – it is said that this honour goes to Elogio del Horizonte (Eulogy to the Horizon) in Gijón – but it perfectly defines the foundations of his conceptual universe. And, of course, it reflects his sentimental relationship with one of his favourite spots in the capital of Gipuzkoa. “This place is the origin of everything. It is the true author of this work: I merely discovered it. The wind, the sea, the rocks: these come together to play a decisive role. It is impossible to create a piece like this without taking the environment into consideration,” said Chillida.

A few meters from the Miramar Palace, half-way along the bay, a small granite figure emerges from the ground: Homenaje a Fleming (Homage to Fleming), also by Chillida. At the other end, on the Sagüés esplanade, facing Zurriola beach, is La Paloma de la Paz (The Dove of Peace) a sculpture by Néstor Basterretxea. The San Sebastian City Council asked the artist from Bermeo to create a monumental piece, which was initially placed next to the Kursaal building in 1988, in the neighbourhood of Gros. Years later, the sculpture was relocated to Amara due to the renovation of the Paseo de la Zurriola and the construction of a conference centre.

The sculpture, standing seven meters tall and weighing four tonnes, concluded its journey in 2015 and returned to Gros. This monumental dove, now a symbol against violence, shares aesthetic connections with the logo that Basterretxea created in 1978 for the campaign in defence of the Basque language, ´Bai euskarari´ (Yes to Euskara), promoted by Euskaltzaindia (Royal Academy of the Basque Language). While the initial image resembled ‘a bird of fire, a sort of phoenix rising from the ashes,’ this time, the synthesised image of the dove extends its wings in full flight, calling out for peace and harmony.

Finally, the sculpture Construcción Vacía (Empty Constuction) by Jorge Oteiza awarded a prize at the Sao Paulo Biennial in 1957. Two years later, at the peak of his artistic career, Oteiza announced that he was giving up sculpture. The artist from Orio, 15 years older than Chillida and Basterretxea, was a constant source of surprises.

Fleeting encounters

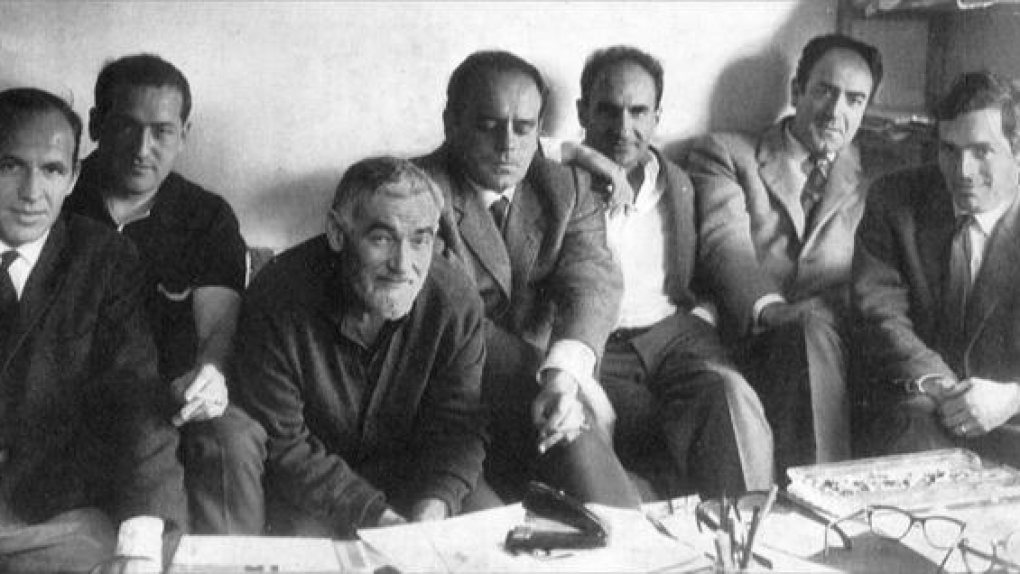

In 1966 Grupo Gaur was created through a manifesto and a collective exhibition held at the Barandiaran gallery in Donostia. It comprised a constellation of the most innovative and avant-garde stars in Basque art. Amable Arias, Rafael Ruiz Balerdi, Néstor Basterretxea, Eduardo Chillida, Remigio Mendiburu, Jorge Oteiza, José Antonio Sistiaga and José Luis Zumeta were the leading members of the cultural movement. That collective venture, conceived during the Franco dictatorship (1939-1975), proved short-lived. Political and artistic disagreements within Gaur led to its dissolution and the closure of the gallery.

Both Basterretxea and Chillida were involved the basilica of Arantzazu (Oñati), a project that turned the religious art of the last century on its head. The adventures and vicissitudes of Arantzazu are impossible to understand without Oteiza´s controversial sculptures – banned by the Bishop of San Sebastián and scandalising the Vatican – but also without the contributions of the other artists. The new church was designed by two architects, Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza and Luis Laorga. Eduardo Chillida made his contribution (the iron doors are his), while notable mentions include paintings by Néstor Basterretxea (depicting the evolution of mankind and the resurrection of Christ) and Lucio Muñoz. The sanctuary project began in 1950 and was not completed until October 1969, when Jorge Oteiza finally installed his apostles on the façade.

More encounters. The Bilbao Fine Arts Museum features a large, suspended sculpture by Chillida weighing 13.5 tonnes, situated outside. Lugar de Encuentros IV (Meeting Place IV) was created between 1973 and 1974 and is part of a series of large-scale works intended for display in public spaces. Since 2000, the square and the entrance hall itself have been named after the Basque sculptor. Basterretxea, in the final years of his life, donated 18 pieces to the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum. These included 17 sculptures made of oak and one of bronze, all part of the Basque Cosmogony Series, which he created between 1972 and 1973. According to the Museum, ‘the works are based on mythological characters, forces of nature and traditional objects from Basque culture taken from José Miguel de Barandiarán´s Diccionario de Mitología Vasca (Dictionary of Basque Mythology, 1972).

Basterretxea: whirlwind of activity in the Bidasoa

In 1958, Néstor Basterretxea moved into a home and studio designed together with Oteiza and architect Luis Vallet de Montano on Avenida de Iparralde in Irun. Over the following decades, the building attracted Basque and international artists alike, becoming a cultural hub for the city and continuing to be fondly remembered with nostalgia today.

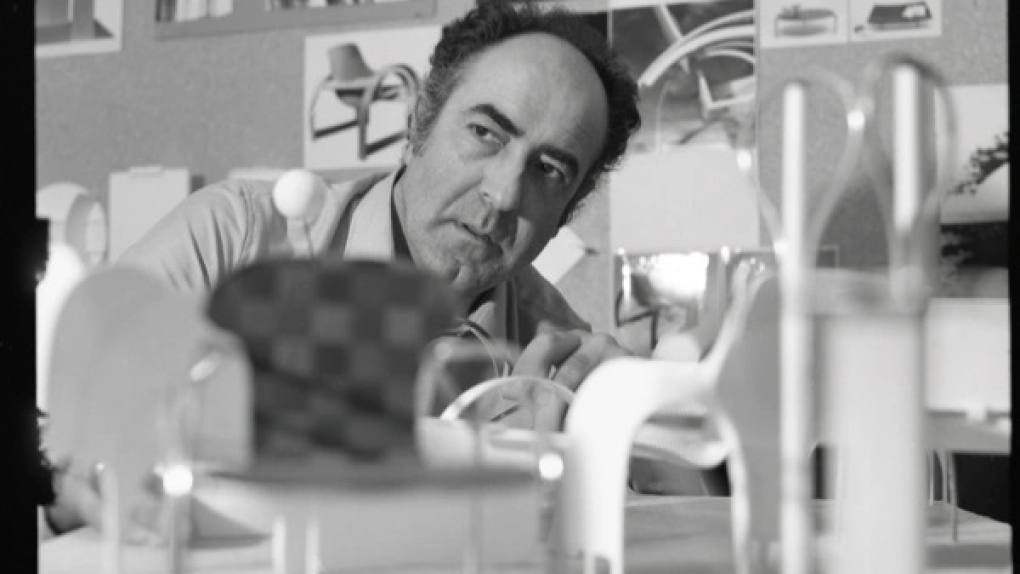

In the Bidasoa region, Basterretxea engaged in intense business and artistic endeavours, expanding his activities across multiple fronts. In 1960 he went from painting to sculpture and became a partner and designer for the modern furniture manufacturer Biok. In 1963 he tried his luck in the world of cinema. Teaming up with filmmaker Fernando Larruquert, together they founded the production company Frontera Films Irún. Among his filmography, Ama Lur stands out, a 105-minute documentary that had its first premiere at the San Sebastian Film Festival in 1968. The film still maintains its mythical aura intact. Conceived as a grand visual poem of the Basque cultural imagination, it faced challenges from Franco´s censorship. One of the censors objected, insisting that the tree of Gernika, a symbol for the Basques, should be shown in bloom rather than covered in snow.

Néstor Basterretxea cultivated a multifaceted universe encompassing design, architecture, cinema, plastic arts, photography, and cultural and political activism. He passed away at his home in Hondarribia at the age of 90.

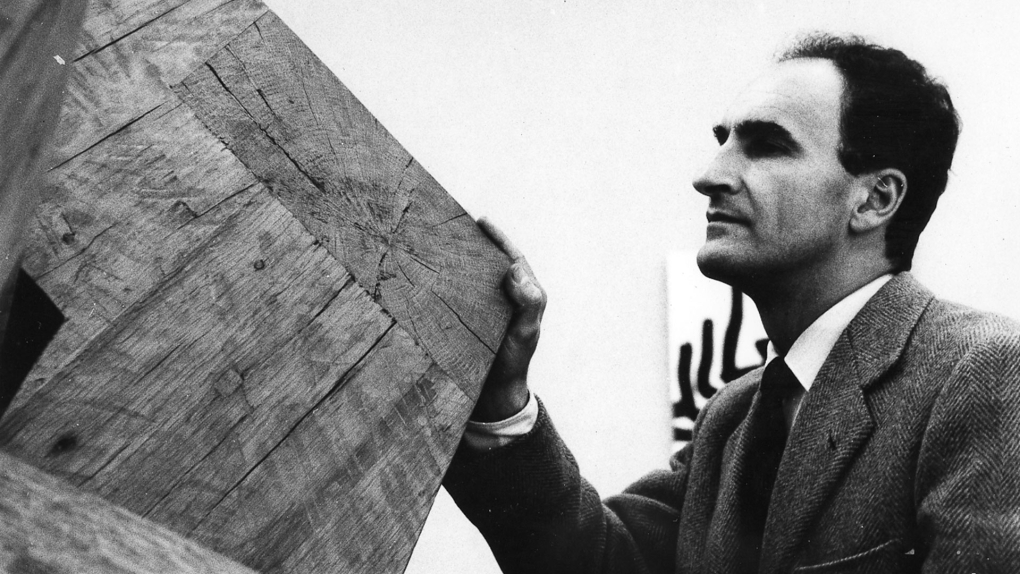

Chillida: Basque and cosmopolitan

Eduardo Chillida went on to international fame. Anecdotally, he was goalkeeper for the Real Sociedad football club until a knee injury brought his promising career to an end. In 1950, at the age of 26, he held his first exhibition in Paris. Throughout his life he received countless significant awards, becoming one of the essential figures in twentieth-century sculpture. His work can be found in museums and both public and private institutions around the world as well as in cities such as Berlin, Washington, Madrid, Gernika and Palma de Mallorca, just to name a few. Chillida embodies the figure of the cosmopolitan Basque artist: “"All places are perfect for those who are suited to them. Here, in my Basque Country, I feel at home, like a tree suited to its territory, in its own terrain but with its arms open to the whole world.”

Tindaya, the sacred mountain on the island of Fuerteventura in the Canary Islands, became his ill-fated endeavor. The project was never carried out. The sculptor from San Sebastian intended to dissect and partially hollow out a mountain in order to create a gigantic cube 50 metres high and 50 metres wide. The Canary Islands government gave the green light to the colossal project in the 1990s, but it never got off the ground. Environmental groups rejected it outright. Chillida died in 2002, although two years earlier the utopia he had dreamed of all his life had come true: the opening of the Chillida Leku Museum, in the beautiful gardens of Zabalaga, his farmhous in Hernani, where his ‘sculptures could rest and people could walk among them as though in a forest’.