Things often happen by pure serendipity, like being born in Poughkeepsie, or working in the editorial office of The New Yorker back in the days when people still read paper magazines. Or like going to Madrid to learn Spanish and falling in love with the Basque language. Which is exactly what happened to Elizabeth Macklin.

Elizabeth Macklin: half a century in a sigh

25 Apr 2022

On the corner of Seventh Avenue and 14th Street, one of New York City´s most dynamic crossroads, sits Coppelia. Run by Mexican-born partners, the Latin diner bears the name of the popular ice cream chain in Cuba. The place is small but cosy and full of charm. You can usually hear English and Spanish spoken interchangeably, and occasionally Basque too, since this is where the poet and translator Elizabeth Macklin has her breakfast. And this is where we have arranged to meet. We order a piping hot café con leche served in large cups and start our journey back in time to 1974.

That was the year Macklin arrived in Manhattan. Her parents, Edward Carlyle Wood and Margaret Jean Herkenratt, had moved from California to Poughkeepsie, New York, where Elizbeth was born, and where her father followed the tech giant IBM when it relocated its headquarters. "There was a joke about IBM´s acronym back then. They used to say, ´I´ve Been Moved´,” she recalls with a chuckle. "In 1952 they sent my father to Poughkeepsie to work with computers." Macklin grew up in a small town, but moved to the Big Apple and soon landed a job on the editorial staff of The New Yorker magazine.

Banning a language seemed very harsh, unimaginable even, and it aroused my curiosity.

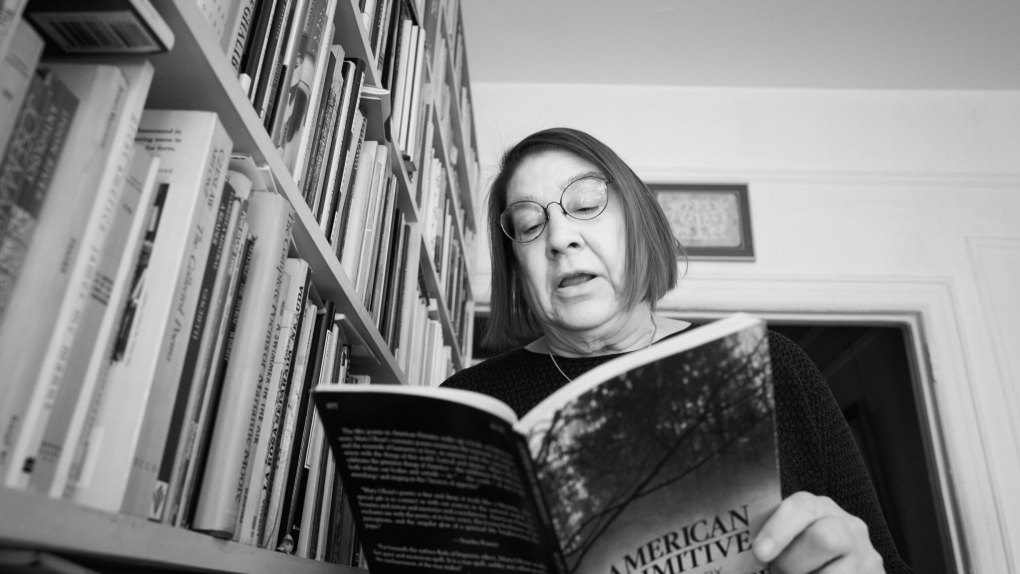

A lot of pen can be put to paper in half a century. However, her well-appointed apartment above the Coppelia diner reflects the events of these decades with more accuracy and precision than the best of poets. Small and elegant, Macklin’s home tells the story of her life through the cracks, crevices, and spirits of her artefacts and furnishings. To the right of the entrance is the library, which houses hundreds of books. A few steps further we find other assorted souvenirs, including a copy of Picasso´s ´Guernica´, which sits atop a loudspeaker and an early edition of ‘Webster´s New World Dictionary’ laid open to reveal its thousands of pages. "It´s the second edition, which dates from 1957. It’s the most beautiful dictionary in existence." It is also Macklin´s preferred tool of trade. To express this or that, so as not to get lost in the tangled labyrinth of meaning, she uses it to look up words. "When I was working on the English translation of Kirmen Uribe´s novel ‘Bilbao–New York–Bilbao’, the proofreader told me that he couldn´t find some words in the dictionary. That´s because he didn´t have Webster´s."

Our language is our passport

As a stateless nation, we Basques do not have our own passport. Our nationality is simply not recognised as such. But while this poses some negative aspects, it is not all doom and gloom. The Basque Country has a strong attachment to its language, Euskara, and the language itself has become the main ‘proof’ of nationality: our language is our passport. After all, the very meaning of the term ´euskaldun´ is ‘Basque-speaking’. It might not be recognised by a customs agent, but it is one of the easiest nationalities to obtain. But let´s move on… How did the poet from Poughkeepsie become a Basque speaker?

When Macklin moved to Manhattan, 14th Street was known as ´Little Spain´, home to many Spanish businesses and restaurants. And, paradoxical as it may seem, Spain and Spanish were the bridge to the Basque language on Elizabeth Macklin´s path. In 1972 she moved to Madrid to study Spanish Philology and in the final years of the Franco dictatorship she started learning Euskara from a friend’s Basque boyfriend from Bilbao. This is how the writer remembers it: "My friend and I learned words like ez [no], bai [yes] and eskerrik asko [thank you], as well as some songs. I remember how we were told to be careful not to sing certain songs in the Madrid metro!” She lived through tumultuous times at university, where much of the anti-Franco movement was brewing. The dictatorship was very severe with the Basque-speaking population. “Banning a language seemed very harsh, unimaginable even, and it aroused my curiosity," Macklin explains.

That desire to learn – and the Amy Lowell poetry scholarship – took her to Bilbao in January 1999, after leaving her job at The New Yorker. Besides signing up at a euskaltegi (Basque language school) and learning the language, Elizabeth has woven together a wide network of Basque writers, musicians, and artists. Hence her friendship with Mikel Urdangarin, Rafa Rueda, Bingen Mendizabal and Kirmen Uribe, who together created the albums ´Jainko txiki eta jostalari hura´ and ´Zaharregia, txikiegia agian´, as well as ´Agian´, a documentary directed by Arkaitz Basterra. Her work translating the novels of Kirmen Uribe and other Basque writers has been essential for introducing Basque literature to the North American public. She is now also a member of *Zart Kolektiboa, a collective of creators and artists, and travels to Bilbao twice a year.

BIO

Elizabeth Macklin (Poughkeepsie, NY, 1952) was editor of The New Yorker for two decades. She is the author of the poetry collections ´A Woman Kneeling in the Big City´ (1992) and ´You ´ve Just Been Told´ (2000). In 1999 she received the Amy Lowell Poetry Travelling Scholarship, given annually to a U.S.-born poet to spend one year outside North America. She chose to spend her time in Bilbao, where she began her studies of the Basque language. She has continued to study the language ever since and in 2002, began translating the poetry of Kirmen Uribe. In 2007 her English translation of Uribe’s book of poems, ‘Bitartean heldu eskutik’ (‘Meanwhile Take My Hand’, Graywolf Press) was published and in 2014 her translation of Uribe´s award-winning novel ‘Bilbao–New York–Bilbao’ was released by Seren Books. This year, Coffee House Press will publish her translation in the USA. In the meantime, she has continued to cultivate her own poetry, both in English and Euskara, thanks to the poetry group Hatsaren Poesia. Her poem ´Reinventing the Conjunction´ (´Juntagailua berrasmatzen´ appeared in issue 10 of the magazine ´Erlea´. Since 2019 she has been a member of the *ZART collective of creators.